Related stories:

"The economic system of New France was inspired by the feudal model, and it continued for many years after the English conquest. The land-owning seigneurs had several obligations. They had to apportion lots so that the land would be farmed. They had to build a grist mill for their tenant farmers, who were called censitaires, or habitants. For their part, the censitaires were obliged to grind their wheat at the seigneur's mill and give him one fourteenth of their flour as a toll." (extract from booklet The Moulin de la Rémy)

The region of Baie-Saint-Paul and Saint-Urbain had been entrusted in 1662 to the Seminary of Quebec which had been parceling it out to settlers ever since. The population was growing fast and in 1806 the Seminary had a wooden mill built on the Rémy to serve its pressing needs. By 1825 however, the wooden mill had fallen in serious disrepair and the Seminary contracted Jacob Fortin to replace it by a much larger stone mill which would include lodgings for the miller and his family. This new mill began operating in 1826-27.

Roger Bouchard

Roger Bouchard

Its first miller was Roger Bouchard from nearby Petite-Rivière-Saint-François, a rather dubious character according to Les Moulins à eau du Québec: du temps des seigneurs au temps d'aujourd'hui by Francine Adam. He appears to have had marital and anger management issues which drove him to an ugly legal dispute with the local priest. I won't get into details but, to put it mildly, his poor wife seems to have had few reasons to be happy in her new home. He operated the mill for 8 years during which it almost burned down (as the story goes, the mill was spared because God agreed to turn the wind around after the priests at the Seminary notified Him of its imminent destruction) and otherwise deteriorated. However, maybe because he fell seriously behind in what he owed the Seminary, when the miller left the region in 1850 to build and operate a sawmill further north, he was considered a wealthy man.

The millers who succeeded him were not as colorful and although their names survived (I was gratified to spot a woman among them, Marie Fortin Simard, a widow who operated the mill from 1880 to 1884 before entrusting it to her sons), not much else is known. From 1902 to 1991, the mill remained in the hands of the Fortin family: Cléophase Fortin was the miller from 1902 to 1909, Robert Fortin from 1909 to 1951 and finally Félix Fortin from 1951 to 1991.

Félix Fortin

(photo from booklet The Moulin de la Rémy)

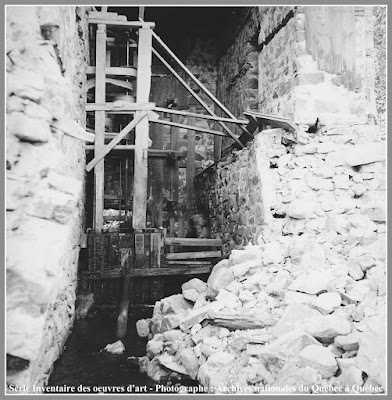

By all accounts, Félix was deeply attached to his mill and cared for it in the best way he could but he didn't have money to make the necessary repairs: the north wall had crumbled, sending stones tumbling down as far as the river. The great waterwheel was gone. The façade had cracked following a series of earthquakes. No longer able to produce flour, Félix kept producing dry animal feed until he retired. The going was tough however as he had to compete with the new industrial mills.

At the time of his retirement in 1991, he had few reasons to believe his mill would ever be back to what it was in its prime, let alone be operated again. But Heritage Charlevoix bought it in 1992 and the rest is history... (see )

As can be seen from the following picture though...

...while the old mill was surrounded by various outbuildings (the barn and the root cellar have been restored already and the outdoors bread oven will soon be reinstalled), there was nothing near it resembling a bakery. Since Frank Cabot's dream was to restore bread to Charlevoix County (see ), a building had to be either found or built. Bent on preserving the county's heritage, Frank opted for the second solution. Heritage Charlevoix purchased an abandoned farm building in nearby Sainte-Irénée, had it sliced in half, and carried to the site on trucks.

Once the bottom part of the house safely set on its new foundations, the ovens were trucked in. Built 27 miles (45 km) away in Jean-Claude Bernier's workshop, these replicas of eighteenth-century French wood-fire ovens each weighed more than 40 tons. I would have loved to show you a picture of the ovens lifted with a crane and set in their assigned spots and, even better, a photo of the old roof flying through the sky to be reunited with the bottom part of the farm house but none is available that I know of and we'll have to be content with a picture of the bakery today.

For all practical info regarding the mill and/or the bakery, please refer to the Moulin de la Rémy's website.

No comments:

Post a Comment