It smelled so wonderfully lactic I couldn't bear to throw away the surplus. So I decided to bake with it.

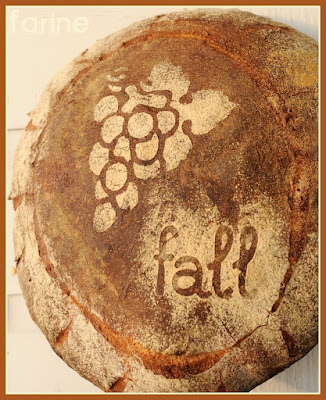

I picked a very simple formula, Jeffrey Hamelman's Pain au levain (Sourdough bread) from the second edition of his book Bread: A Baker's Book of Techniques and Recipes and adapted it a bit. I don't usually bake or eat mostly white breads but I just had to taste my Chicago levain and by using no other flour than all-purpose (except for a smidgen of rye), I was hoping we would be able to savor it in all its glory. I am glad to say it worked (thank you, Jeffrey!). The bread has zero acidity and a delicate lactic aroma. It smells like the first breeze of spring over the prairie. Not that I ever saw the prairie or what's left of it but I am blessed -or cursed, depending on the occasion- with a vivid sensory imagination and the starter is from the Midwest after all. Since the prairie is what I saw with my mind's eyes when I inhaled the breath of the proofed dough, I couldn't resist stenciling one of the loaves with flowers and calling it the Prairie Loaf. And when that loaf came out of the oven in full bloom, I knew I had to bring it to my favorite plant whisperer, the friend who helps make our CSA such a happy place (thank you, Rita!). I shaped the other loaf as a bâtard in memory of the long rustic loaves my eighty-year old grandfather used to go get from the nearest village on his Solex motorized bicycle.

Baking on an impulse is fun but it has its drawbacks, one of which being that you have to adapt to what you have on hand. After feeding the starter, all I had left was about 160 g of mature levain. You know me, I am hopeless at math. With a calculator, I could have figured out the relative weights of the other ingredients but it would have taken a while and I knew I didn't have to because I could count on BreadStorm (the software I am using for my bread formulas) to do it for me.

Using the drop-down scaling menu, I entered the amount of flour in the levain (which I calculated by dividing 160 g by 175 then multiplying by 100) and in a flash, the weights of the other ingredients were recalculated and I was ready to mix. Sweet! Thank you, Jacqueline and Dado Colussi for having thought up this amazing software, and, Dado, a thousand thanks for this beautiful starter! And as you probably guessed, dear readers, there is a Meet the Bakers Dado and Jacqueline Colussi in this blog's near future. Thank you for your patience!

Ingredients

- Build the levain the night before

- On the day of the bake, mix levain, water and flours until incorporated and all the flour is hydrated (I mixed by hand)

- Let this shaggy dough stand, covered, for 30 to 60 minutes

- Add the salt and mix until the dough is cohesive and supple, adding water if necessary to obtain a medium consistency

- Transfer to oiled container and cover

- Do two folds at 50-minute intervals

- Let ferment for another hour and place in the refrigerator for up to 24 hours (it might become acidic if you wait any longer)

- Pull the dough out when ready to shape and proof

- Divide in two and shape as desired

- Proof until ready (the length of the proofing depends largely on the room temperature. A loaf is ready to go in the oven when a small indentation lingers when you palpate it gently with one finger)

- Bake for 35 to 40 minutes in pre-heated 450°F/232°C oven, applying steam at the beginning

- Cool on a wire rack

- Enjoy!