Customer education begins in the window:

"People need to learn to live within the Earth's finite resources, they need to pay attention to the weather, to the climate. Once a crop is all in, that's it for the year. In the fall, we use apples and pears in our tarts and cakes, in the winter, lemon, chocolate, caramel and apples (they keep well); in March, we work with dried fruit. Then spring arrives, bringing back first strawberries, then apricots. When someone asks for a fraisier (a fresh strawberry cake) in December, we explain why it can't be done. Our sandwiches and other snack food follow the seasons as well. We offer thick vegetable pies in the fall when varietal diversity is at its peak. As soon as tomato season is over in France, grated raw root vegetables (carrots, beets) or céleri rémoulade (grated celeriac in a mustardy mayo dressing) replace tomato slices in our sandwiches. New customers are baffled. We explain. That's when consumer education happens. Some will never learn, they go elsewhere. Most stay. We have lots of students, many families, old people who are the pillars of our community. Some come three or four times a day: for croissants in the morning, for a salad or a quiche at lunch, for bread at any time." Listening to Guillaume (who, while talking to me non-stop in the bakery's kitchen, is also hand-mixing mayonnaise and chopping and grating vegetables for salads and sandwiches), I feel a sudden longing for a life where I too might be able to stop four times a day by my neighborhood bakery...

The bakery gets its flour from Moulin Trottin, a mill whose owner largely shares Guillaume's outlook on territoriality and the environment: the flours Guillaume buys from him are all French and all organic. He shuns such exotic grains as kamut and quinoa: "They come from too far away. Using these flours makes no sense economically-, biologically- or environmentally-speaking. So we do without. Besides wheat, the flour we use the most is petit-épeautre, also called engrain (emmer). Grown in central France (the one from Provence is too expensive) and rich in minerals, it is redolent of our terroir français. Since it is low in gluten and absorbs a lot of water, we have developed a special formula and technique to make the best possible use of its characteristics and to showcase its unique flavor. It is quite popular with our customers."

"We use no grand-épeautre (spelt) at all. It is too close to wheat, especially in gluten-content, to be of much nutritional interest." Guillaume stops chopping for a minute. "Gluten intolerance is a modern ailment, a direct result of wheat selection which has consistently favored high-gluten varieties: today wheat can contain up to forty-three percent gluten. Twenty years ago, the percentage was twenty-five percent. There is naturally much less gluten in ancient wheat varieties, such as the ones that are currently being reintroduced in some parts of southern France." His face takes on a slightly mournful expression: "I guess gluten-free baking has a future in this country, sort of." Chopping resumes at a faster rythm.

The loudspeakers are going full blast in the shop and kitchen; Guillaume and Suat, his sale associate, are moving briskly. It is mid-morning. Their shift has started early but not as early as Luc's, who is nevertheless still busy downstairs in the bread lab. The phone rings, the greengrocer is on the line. Guillaume, who is dexterously filling mini-tubs with the salad he just made, wedges the phone between cheek and shoulder and places an order from a list seemingly embedded whole in his memory: "Flat parsley, Reine de Reinettes and Golden apples, leaf celery, eggs, etc." He goes on and on. The seller is a cooperative of producers and everything is organic.

I ask about dried fruit and nuts. "We buy organic French walnuts. I'd love to buy French hazelnuts as well but we just don't produce enough. The best hazelnuts come from Italy. Unfortunately ninety percent of Italian hazelnuts are gobbled up by a huge industrial confectioner. " He shakes his head: "And that's how the best hazelnuts in the world end up in the worst candy in the world. " He looks dejected for a minute but he soon brightens up: "Right now I am looking for a producer of AOC chestnut flour in Corsica but this year's crop isn't completely in yet. I have to wait. Meanwhile I use the Markal brand. My rule is to go as close to home as possible to buy the best I can find: almonds from Spain, hazelnuts, figs and apricots from Turkey."

One thing is for sure: no truck ever lumbers up to Le Pain par nature to delivers frozen pastries and viennoiseries; no order is ever placed for strawberries from Spain, Africa or South America or from anywhere but France, for that matter; mangoes, pineapples, sesame seeds and pistachios never darken the door. Ninety-two percent of the fruit and vegetables used at the bakery is grown in France and organic. Milk and eggs are organic too. But, Guillaume explains, "Organic is becoming a business, and nowadays the only organic butter available in France comes from Holland. It makes no sense to use Dutch butter when we ourselves make the best possible butter for our croissants!" So he buys Montaigu, a conventional AOC butter from Charentes-Poitou.

Suat Adiyaman, Luc Poggio and Guillaume Viard

Among the special breads on offer on this particular morning, I spy the Cambrousse, a country bread...

...the Pain des champs...

... and a few glorious miches...

I also spy also viennoiseries such as the airy chausson aux pommes below (filled with homemade applesauce)...

...the friand maison (a house pâté made with ground meat -veal, beef and chicken- and fresh herbs)...

...or crumbly pains au chocolat aux amandes (twice-baked chocolate almond croissants)...

Despite using all organic ingredients (save for butter, oil and vinegar), Guillaume and Luc keep their prices reasonably competitive. The Bioguette goes for one euro (a non-organic baguette costs an average of € 0.85 in Paris, € 0.95 in the neighborhood) and the Tradi-Bio for € 1.20 (against an average of € 1.10 for a conventional baguette tradition in Paris, € 1.15 in the neighborhood). Sandwiches and salads are a bit more pricey than elsewhere, reflecting the added cost of the ingredients but they still fly off the shelves. "People come for the taste. They may grumble about the price but they come back." Guillaume hands a stack of covered salad containers to Suat who takes them into the shop. Noon is fast approaching, the lunch crowd will soon arrive, re-stocking is in-order.

Full trays of just baked snacks are waiting to be displayed...

Roullos made with rolled out tradibio dough smothered with organic ham and cheese

sometimes made instead with julienned veggies or shredded chicken and cheese

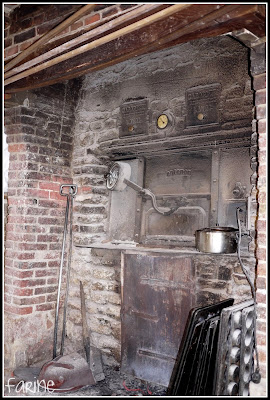

Guillaume met Luc at La Boulangerie par Véronique Mauclerc, an organic bakery which I remember visiting it a few years ago, awed by the diversity and flavor of the offerings. (For a picture of Guillaume in front of Mauclerc's woodfire oven, one of only three still in existence in Paris, click here). There is pride in his voice when he adds: "I trained him myself. Now he runs our bread lab."

As for Guillaume, he started as an apprentice in a bakery in Central France (where he is from). Sadly the boss never allowed him to touch anything but a broom and a mop and he spent his days cleaning the floor. So he joined Les Compagnons du Devoir, became a baker, did the customary Tour de France, and after trying his hand at pastry, cooking, and other trades went back to bread when hired by Veronique Mauclerc. "Not only did I learn a lot from her about organic baking but she also taught me self-reliance. At one point though we found ourselves disagreeing about some fundamental choices and we parted ways. I went down South to get my driver's license and started thinking about the bakery I was dreaming of opening one day. I worked a bit for Eric Kayser, a fellow Compagnon and my then-idol (I learned a great deal from his three textbooks). Then Luc and I decided to become partners. It took us more than two years to put the project together: a year and a half to write the business plan, six months to find financing then a year to locate the bakery we wanted. We found our current premises (where a bakery has been continuously in operation since 1904) through word-of-mouth. There were many other interested buyers but the owners liked us from the get-go. So they sold to us. We opened on November 5, 2012 and did well right away: sales volume increased by 50 to 60% the first year compared to the sellers' turnover of the year before (to be fair, they weren't getting any younger and didn't have their heart in it anymore). Most of their customers stayed with us. Le Pain par nature is a neighborhood bakery and we love it that way."

Guillaume is very proud of the fact that he won tenth place earlier this year for his tarte aux pommes (apple tart) in a Paris-wide competition. "I was raised in rural France and we grew most of our food. All organic of course. We knew no other way. I still do everything the way we used to. For instance, I make my crème pâtissière (pastry cream) from a recipe given to me by a great-aunt. I don't change a thing." When he was a child, he baked cakes every Sunday, so when he joined the Compagnons, he was hoping to become a boulanger-pâtissier (bread baker/pastry chef) but admission was based on competitive exams and "I could only apply to one. I picked 'boulanger' because the trades were listed in alphabetical order and it was the first to come up. I have no regrets: pastry is a very rigorous and technical craft. That's not who I am. I work on instinct, on feeling. But I still like pastry. Although maybe I like cooking even more."

Le Pain par nature is a different kind of business: "We chose to make it a cooperative, which means that the focus is on the business itself, not on the capital. We are required by law to keep it growing as opposed to getting the most money out of it and, again by law, we cannot be anything but salaried employees. Right now the bakery officially has two employees, Luc and myself. Suat - who is a landscape artist by trade - came on board at a later stage, when the company he worked for went out of business. He is expected to soon become a partner."

"We all share the same ideas. Luc was born in Paris but he is keenly aware that organic is the way of the future. Our dream is actually to one day open an école de boulange (a baking school), maybe in my childhood home if we can swing it as it is fairly large and comes with a fruit and vegetable garden. We would just need to build a classroom. We would adopt a holistic approach and teach all aspects of the trade: working with organic ingredients only, we would make sure the apprentices know where everything comes from. They would grow the produce they would use. We would build a mill to help them understand flour. They need to see by themselves that wheat requires time, technique and terroir to grow, that the land has its own nature, origin and history, that life has meaning and that bread is alive. We'd seek accreditation but we couldn't get it, we could remain a private trade school: our graduates would just have to sit for the public exam to obtain their official diplomas. Whether or not we ever open our dream school one day, we already live and work by our principles and I like to think that our bakery is twenty years ahead of our times."

I close my notebook and Guillaume selects a well-baked Tradi-bio among those which have just come out of the oven. He hands it to me. It makes a lovely crackling sound: "Taste it later when it has cooled down a bit". I already know that it will taste just the way it looks, as an honest to goodness baguette, ready to play second fiddle to whatever tasty food will be put on the table but whose crust and crumb make it ideal for that most cherished goûter (afternoon snack) of my childhood: bread with a bar of chocolate inside. The torch is passing to a new generation and it is a lovely feeling.