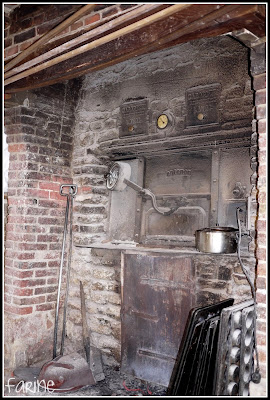

The notion of terroir is of supreme importance to the artisans we met that day. Erik the baker moved to the country to be closer to the wheat. He started using a small mill close to his bakery but the miller moved away. So for now he gets his flour from le Moulin de Persard in Western Normandy. When Manu realizes his project of growing and milling wheat for the bakery however, the full circle they both have been dreaming of all along will become reality.

(photo courtesy of our friends at Tree-Top Baking, along for the visit)

Lin Bourdais, 47, has been making organic cheese for 6 years at Bois Canon, the farm he bought from his parents. He has thirty cows who produce milk all-year round on 52 ha (128 acres) of land. He sells his cheese on two open-air markets (Mézidon and Caen) as well as to a few natural food stores and to CSA's. This year he had to deny cheese deliveries to other stores: the farm doesn't yield enough milk to make more cheese (it takes 450 liters of milk to make 45 kg of cheese) and he doesn't want to buy milk elsewhere, even from a neighbor, because he wouldn't know first-hand what the cows had eaten and wouldn't be able to control the flavors. He works with the tastes of his terroir and wants it no other way.

He has help: Sophie Martinet, who became his business partner a year-and-a-half ago; Xavier, who is interning at the fromagerie and David, an expert cheesemaker who came to replace him when he had to leave for a while (sorry, I don't have last names for Xavier or David). Three people need to work full-time to maintain production levels.

Now Lin's cheese isn't typical of what Normandy usually produces, i.e. soft cheeses (such as Camembert, Pont-L'Évêque or Livarot). Tommes are normally to be found in mountainous areas, such as the Alps or the Massif Central, and they are often low in fat. Lin's isn't. He uses full fat raw milk and the resulting cheese is wonderfully tender. The one he cut open for us had been aging since the previous June (since we visited in March, it was about nine months old). It gets better as it ages but Lin says the demand is such that it is difficult to keep enough tommes around to age them.

He currently sells cheeses made in January 2012, November 2011 and June 2011. He says that once he kept a cheese for two and a half years to sell at Christmas time. He put it for sale at twice the regular price -which is €12/kg or a little bit under $8 per pound- and it flew off the table.

Lin's tomme is an uncooked pressed cheese (like Cheddar). I know this is normally a bread blog but just in case you are interested in cheese (I know I am: wine and cheese have got to be my favorite food pairings), take a quick look at how it's made (the first photo is kind of foggy because it was very warm in the room and we were coming from outside, so glasses and camera lenses misted up right away!).

He has help: Sophie Martinet, who became his business partner a year-and-a-half ago; Xavier, who is interning at the fromagerie and David, an expert cheesemaker who came to replace him when he had to leave for a while (sorry, I don't have last names for Xavier or David). Three people need to work full-time to maintain production levels.

Now Lin's cheese isn't typical of what Normandy usually produces, i.e. soft cheeses (such as Camembert, Pont-L'Évêque or Livarot). Tommes are normally to be found in mountainous areas, such as the Alps or the Massif Central, and they are often low in fat. Lin's isn't. He uses full fat raw milk and the resulting cheese is wonderfully tender. The one he cut open for us had been aging since the previous June (since we visited in March, it was about nine months old). It gets better as it ages but Lin says the demand is such that it is difficult to keep enough tommes around to age them.

He currently sells cheeses made in January 2012, November 2011 and June 2011. He says that once he kept a cheese for two and a half years to sell at Christmas time. He put it for sale at twice the regular price -which is €12/kg or a little bit under $8 per pound- and it flew off the table.

Lin's tomme is an uncooked pressed cheese (like Cheddar). I know this is normally a bread blog but just in case you are interested in cheese (I know I am: wine and cheese have got to be my favorite food pairings), take a quick look at how it's made (the first photo is kind of foggy because it was very warm in the room and we were coming from outside, so glasses and camera lenses misted up right away!).

The first few weeks, the cheese is washed two to three times a week and at the very beginning, it gets flipped over at each washing. Afterwards, the washing occurs only about once a week: it starts from the top shelves (where the older cheeses reside) so that the bacteria naturally occurring on the rind can trickle down and bring more flavor to the younger tommes. The shelves have to be made out of white wood (ash tree, Norway spruce, fir tree). Any other wood would impart an unwelcome taste to the cheese.