The 2014 Grain Gathering (formerly known as the Kneading Conference West) took place last week on the gorgeous grounds of Washington State University Agriculture Research Center in Mount Vernon, Washington. It was the fourth of these events and as we now live in California (I had sent in my registration long before I knew our move would be a done deal by the time mid-August came around), I truly thought, before flying up, that this one would probably be the last one for me.

After all, I do get it: eat locally and seasonally, be gentle with the landscape by favoring organic or at least environmentally friendly agricultural methods and always remember that farmers need to make a living too (after all, if there were no more farmers, there'd be nobody between us and Big Food, a thought too scary to contemplate). So I had more or less convinced myself that this year's event would be mostly a rehash and that having attended the first four ones, I was done!

Well, I am happy to say that I was wrong and that I flew home with dreams of the fifth Gathering dancing in my head! The name of the event was changed from Kneading Conference to Grain Gathering because, as Steve Jones (wheat breeder and Director of the Center as well as of the Bread Lab) puts it: "Nobody kneads anymore." Plus bakers are not the only ones interested in grain: farmers, millers, breeders, brewers, etc. flock to Mount Vernon as well. In fact, more than anything, the "gathering" dimension is what will keep me coming. I love the energy and dynamics of encounters with participants from all over (twenty American States, three Canadian Provinces, the United Kingdom and South Africa.) I love it that bread isn't the only focus, that classes, lectures and workshops on milling, malting, brewing, breeding, building earth ovens, transforming a stationary bike into a grain mill, etc... are all mobbed as well.

For an idea of the scope of the Gathering, you may want to take a look at the schedule. In an ideal world (where Time wouldn't exist or if it did, wouldn't be linear), I would have attended all classes, lectures, tours and workshops concurrently but as it is, I had to choose. So I forewent production baking (even though the workshop was run by two bakers I greatly admire, Mel Darbyshire from Grand Central Bakery in Seattle and Scott Mangold from Breadfarm in nearby Bow-Edison), the roundtable on the farmers' perspective, the one on milling and nutrition, the tour of the orchards and gardens, the visit to the wheat, barley and buckwheat fields, the talk on the science of bread, and many more that I won't even mention because I feel bad for missing them all over again, but if you check out the program, you'll have a good idea of what I am talking about.

In the end I opted for workshops that spoke louder than others either to my imagination or to my practical side or more often than not, to both. I attended all three of Naomi Duguid and Dawn Woodward's instructive and stimulating demos on the use of whole grain in everyday baking and cooking. I watched Richard Miscovich score proofed loaves before loading them in a wood-fired oven (Richard is an extraordinary baker and instructor and seeing him work is both a teaching moment and an experience you are not likely to forget.) I only caught the tail-end of Jeffrey Hamelman's pretzel workshop but still, I arrived at the wood-fired oven in time to see him score the pretzels (or not as he said it was a matter of personal preference) and hear most of his account of the tough love teaching methods of his German baking instructor.

I listened to a very interesting presentation by two high school students who won first place in the food science category at the 2013 Washington State Science and Engineering Fair for their project on fermentation and gluten.

I attended a lecture on natural leavening which went largely over my head but gave me the great pleasure of finally meeting microbiologist Debra Wink and hooking up again with Andrew Ross, professor of crop and soil science and food science at Oregon State University. I spent time with beloved friends, connected with other bloggers, met bakers, writers and Facebook friends I had never seen in person before, I took part in the Bread Lab's tasting of four different wheat varieties, all grown in the Skagit Valley, and I ate my way through three days of the most seductive event food imaginable.

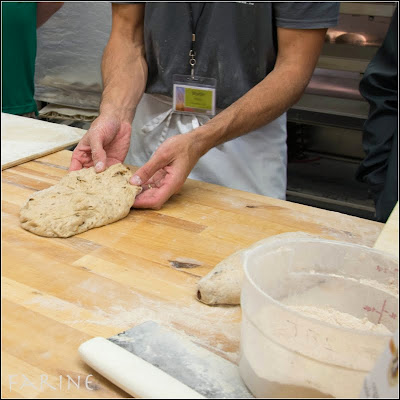

In between, I took pictures (or, shall I say, "gathered" images) with joyful abandon (making up for last year when my left arm was in a cast.) I will post some (okay, a lot) of them in the coming days. If there are any recipes you are specifically interested in on the basis of the photos, please let me know and I'll ask for permission to post them. As far as I know, no pizza recipe is available but from the look of the ones I saw, the only ingredient that appears absolutely necessary is a boundless imagination!

Related posts

Showing posts with label Kneading Conference West. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Kneading Conference West. Show all posts

Monday, August 25, 2014

Saturday, October 12, 2013

Fig-Anise 50% Whole-Wheat Bread

This Fig-Anise 50% Whole-Wheat bread was developed with the help of baker Martin Philip during the Creating Signature Breads workshop at the Kneading Conference West 2013.

Ingredients

By percentages

By weights (for four loaves)

Method

For those of you who are using BreadStorm (including the free version), please click on this link to import the formula so that you can scale it up or down as desired.

Ingredients

By percentages

By weights (for four loaves)

Method

- Using mixer on first speed, combine flours, water and levain until incorporated (reserve about 10% of the water for later adjustments if needed)

- Sprinkle salt and yeast on top

- Give a 15 to 30 minute rest (we didn't have time to do a longer autolyse at the Kneading Conference but a longer one would have been better)

- Turn mixer back on to incorporate yeast and salt

- Check hydration: dough should feel supple. Adjust as necessary

- Mix 2 min on second speed until gluten is fully developed

- Put in anise seeds, soaked grains (don't strain them) and figs

- Mix to combine on first speed: dough will fall apart first, then knit itself together

- DDT: 78°F

- Fermentation: 3 hours with one fold at 45 min

- Scale at 560 g

- Pre-shape as a loose boule (you have to be really gentle with this dough as it contains a lot of whole wheat and could get really dense if manipulated briskly)

- Shape as batards or tear-drops (to mimic shape of fig). If using a tear-drop shape, fold one end of the batard over itself as illustrated below

- Proof seam-up in floured bannetons or on floured couches for 45 min to one hour (use whole-wheat or whole-spelt flour)

- When loading on a peel, give each tear-drop loaf a slight curve to one side

- Bake for 32 to 35 min at 450° F, with steam

- Cool on a rack

- Enjoy!

For those of you who are using BreadStorm (including the free version), please click on this link to import the formula so that you can scale it up or down as desired.

Kneading Conference West 2013: Creating signature breads

Martin Philip, our instructor for this workshop, is a baker and the bakery operations manager at King Arthur Bakery in Norwich, VT. According to his bio on King Arthur's website, in previous lives, he was a professional opera singer and worked in investment banking. I never met him in these past avatars. I only know him as an accomplished baker (the flavor and crunchiness of the straight dough baguettes he handmixed for us the following day while our other dough was fermenting put to rest once and for all any preconceived idea I might have had on baking without a pre-ferment). Martin is also an excellent instructor. A firm believer in the Socratic method, he favors collaboration and the meeting of minds over didactic teaching and magisterial pronouncements, yet he keeps a firm hand on the discussion and never lets it go out of focus. It surely works for me!

The goal of the workshop was to design a bread as a group. Martin explained that before we could even start, we had to make a few choices. What kind of a bread did we want? What ingredients were we thinking of using? What did our production schedule look like? The combinations were almost infinite as Martin demonstrated from the deck of cards he uses as prompts. A baker may want/need to:

- Showcase seasonal flavors

- Use grains that are available locally

- Diversify his or her offerings

- Satisfy a customer request (for a specific taste or nutritional benefit)

- Challenge himself/herself by using a new technique or a different type of flour

Based on the flour(s) to be used, the baker needs to make decisions regarding:

- Type of pre-ferment (if using)

- Hydration

- Type of leavening

- Mixing

- Bulk fermentation

- Shaping and scoring

- Final proof time

- Bake temperature and duration

FLOUR

- If using a weak (low protein) wheat flour, the baker might choose to pre-ferment all of it (i.e. to hydrate all of the weak flour with some of the water in the formula, adding a bit of yeast and salt, and to let it ferment anywhere from three to twelve hours) in order to make the dough stronger

- If using a strong (high protein) wheat flour, an autolyse is the way to go as it helps boost extensibility. It is highly recommended for baguette dough

- If a niche flour (buckwheat, einkorn, legume, quinoa, grapeseed, sprouted wheat or spelt, durum, sorghum, kamut, mesquite) is to be used, thought needs to be given to ways to get the desired crumb structure

WATER

- Hydration is pretty much dictated by the type of flour(s) to be used

LEAVENING

- The baker might choose to use either commercial yeast or a starter or maybe both. It all comes down to the kind of flavor s/he is looking for. Baguettes, for instance, have a very different flavor profile when made with liquid levain as opposed to commercial yeast.

- If using a levain, build schedule needs to be a consideration

- Liquid levain and poolish are usually made with white flour but some whole flour can be used as well. A pre-ferment containing whole grain will be more active: it might therefore require the addition of a bit of salt. A white poolish or levain is more predictible.

AUTOLYSE

- An autolyse is an optional step in which all the flour and most of the water in a formula are incorporated in the absence of either yeast of salt until the flour is thoroughly hydrated. This somewhat shaggy dough is allowed to rest for a mininum of twenty minutes before the baker proceeds with the mix proper. The goal is to jumpstart both gluten development and enzymatic activity

- Commercial yeast is never added to the autolyse but when a formula calls for poolish and/or liquid levain, the poolish and levain are added to the flour and water in the autolyse (flour wouldn't hydrate properly otherwise since they contain a large part of the total water in the formula)

- Doing an autolyse is highly recommended if the dough is to be hand-mixed

- But even if using a mixer, an autolyse is an excellent way of developing the gluten without overprocessing the dough and risking loss of flavor

MIXING

- What type of mix is best for the bread the baker has in mind? Short? Improved? Intensive?

- Generally speaking, today many artisan bakers choose to mix the dough very gently and to rely on folds to develop the strength of the dough during fermentation

BULK FERMENTATION

Decisions need to be made regarding:

- Time: if the dough is machine-mixed, total fermentation time might need to be reduced

- Number of folds (usually based on an evaluation of the dough consistency)

The back and forth was most informative. For ease of reference, Martin's comments are presented in bold and in a different color. Please keep in mind that all percentages are given in relation to the amount of flour, always expressed as 100% (for more on bakers' math, please refer to the post entitled BreadStorm)

- Participant: Could we make a 100% whole wheat bread?

Martin Philip: Since we are going to use figs (a heavy ingredient) it would be preferable to use a fair amount of white flour in order to optimize crumb structure. Going 50% white 50% whole wheat would be a good compromise - Participant: What proportion of figs should we use?

Martin Philip: Since the figs we just bought are moist and don't need to be soaked, we could go anywhere between 25 and 35%. Back home it might be worthwhile to try and make one bucket of dough with 20% figs and another with 30% and then decide which one works best. If opting for another dried fruit, keep in mind that raisins, currants, pears and apples all pull water from the dough unless quick-soaked in boiling water before incorporation - Participant: Could we leaven the bread entirely with liquid levain?

Martin Philip: Sure! Back at home or at the bakery you can, but because of time constraints during the Kneading Conference (due to limited oven space), we will need to add a bit of yeast. Another reason to add yeast is that figs have a high sugar content. Sugar being hygroscopic, it tends to slow down fermentation by pulling water away from the yeast

Tip: if you are making one single dough with different breads in mind, take out the portion you need to make the fig bread and add a bit of yeast to that, keeping the rest of the dough yeast-free for other purposes - Participant: How liquid is the levain we are going to use?

Martin Philip: We will be using a levain hydrated at 100% but at the King Arthur Bakery, the liquid levain is kept at 125%-hydration - Participant: Could we use a firm levain?

Martin Philip: The bright acidity of a firm levain might be a bit assertive for a fruit bread but it might be interesting to mix and match liquid and firm levains or to use a liquid levain and a biga. All elements need to be balanced. Is the levain acidity kept in check by the sweetness of the figs? Experimenting is the way to go - Participant: Could we add in a bit of rye levain?

Martin Philip: We certainly could but if the levain is going to sit all night before we mix the bread tomorrow morning, it might be best to stick to wheat (rye develops faster and may cause the levain to peak before we are ready for it). Another consideration to bear in mind that a sour rye would add acidity - Participant: How much levain should we use?

Martin Philip: The percentage of total flour used in the pre-ferment affects both the functionality of the dough and the flavor of the bread. It is one of the most notable feature in any formula. A high proportion of levain tends to make the bread denser. The ideal in this case would be to use about 18% levain although at the Kneading Conference we will have to use 30% because of time constraints - Participant: Could we make miches?

Martin Philip: Better go for a smaller shape in order to maximize caramelization. A tear-drop shape that would emulate the contour of a fig would be visually pleasant for this bread - Participant: What hydration should we go for?

Martin Philip: No need to reinvent the wheel. The best way to determine hydration when creating a new formula is to look at existing formulas for similar types of breads and see what percentage of water they use. A good starting point for this particular bread would probably be 74-75%. In any case, the baker needs to monitor dough consistency throughout the mixing, keeping a container of water close at hand - Participant: Could we use a soaker?

Martin Philip: A soaker would be a great addition. If you opt for soaking grains such as wheat, barley or rye chops for an extended period of time at room temperature, bear in mind that you need to use a bit of salt or the soaker will be off by the time you are ready to mix. For best flavor, toast the grain, then let it cool, crack it in your mill, add water and soak overnight. In this formula, we are going to use wheat because that's what we have available but back home you may want to try other grains and see which one works best for you - Participant: How much water should we use in the soaker?

Martin Philip: A good ballpark figure for hydrating cracked grain is 120% (meaning a baker needs to use 120 units of water for 100 units of grain). The water used to hydrate the soaker comes out of the total dough water. Same thing for the water used in the levain - Participant: If using a spice such as anise seed, what percentage should we go for?

Martin Philip: One percent is usually the way to go. Remember to always toast aromatics before incorporating them in a dough. Use a heavy metal object to bust up the anise seeds a bit after roasting - Participant: How much salt should we use? Two percent?

Martin Philip: Because of the high percentage of figs and cracked wheat, 2% salt might be a bit low

The (almost) three-hour brainstorming ended too soon for my taste. I could have gone on listening forever! Martin explained that the next step would be for him to work out the formula on his computer based on what had been discussed and to feed the levain. He would mix the dough the following morning, so that dividing, shaping and baking could start in early afternoon.

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Kneading Conference West 2013

It is hard to say what I enjoy most at the yearly Kneading Conferences West: the bucolic setting (the orchards, gardens and fields surrounding Washington State University Research and Extension Center at Mt. Vernon, Washington), the learning opportunities (the instructors are invariably top-level), the discovery of "new" flavors through the local revival of age-old varieties of grain, or the networking (bakers flocked in this year from ten different states, including Alaska and Pennsylvania, many came from Canada and an adventurous soul even made it all the way from South Africa). All I know is that each time I go home re-energized and eager for more.

The only downside to such inspiring events is that they are also exercises in frustration! Take a look at the schedule for this year and tell me you wouldn't have be tempted by pretty much each and every one of these lectures, classes, workshops, and visits. I know I was. Never more than at a Kneading Conference do I regret that human beings haven't been graced with the gift of ubiquity. Oh, well...

In 2011 and even more so in 2012, I followed the grain, trying to get a better idea of the ways bakers could help revive and sustain farms in their communities by sourcing ingredients close to home and learning to work with heritage crops, "liberating" the aromas of their terroir in the process. This year, I went for the bread.

I picked the two-day class on creating signature breads, taught by Martin Philip, a baker and the bakery operations manager at King Arthur Flour in Norwich, Vermont (more on the class in an upcoming post).

I also picked the hamburger workshop taught by Mel Darbyshire, head baker for Grand Central Bakery in Seattle. The focus was on developing buns that would be both handsome and wholesome, and Mel nailed it for sure. I never knew such plump and tasty beauties could actually be good for you! I'll post pictures and the formula as soon as I can.

Finally, on the last day, I sat in for a fantastic lesson on the science of bread, taught by Lee Glass, a passionate home baker and a physician with a keen interest in the chemistry that underlies baking. While I took copious notes, I would be hard put to convey what I heard in a comprehensive and scientifically meaningful manner. So I won't attempt it. Instead and with Lee's help (which he kindly agreed to provide), I will try to put together a few posts on what goes on behind the scene at various stages of baking. If all goes well, it will be a project for the long winter months.

The Conference wasn't entirely focused on technique and science though. Other participants chose different classes. For a broader perspective (and way more pictures since operating the camera with a cast turned out to be a bit of a challenge), you may want to check out the links provided at the bottom of this post.

Darra Goldstein kickstarted the Conference with a welcome reminder of bread culture through the ages. I already knew Goldstein, who teaches Russian at Williams College and is a founding editor of Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture, as the author of A La Russe: A Cookbook of Russian Hospitality, a marvelously nostalgic book which followed me cross-country when we moved west. But I didn't know she was also a bread aficionada (she even owns and operates an Alan Scott wood-fired oven).

There was fervor in her voice as she evoked the traditional Russian stove: made of brick and covered with stucco, it can fire to a very high temperature and since it releases heat very slowly, it can be used reliably for a variety of dishes as it cools. First comes the rye bread, dark and fragrant, then soups and porridges, and finally when the heat is almost a memory, the fermented dairy products.

Slow and beautiful, the stove was always seen as a life-giving force and controlling it was an art. But it would be a mistake to romanticize bread: much of Europe was always on the verge of famine. Putting a loaf on the table required a lot of manpower and was back-breaking work, often done in the dark bakeshops where the only light came from the oven, as attested in the work of numerous painters, notably Millet in France.

Recalling how difficult it had been for her to adjust to life in the Soviet Union as a graduate student, Goldstein said the only thing that kept her from flying back home was Russian hospitality or "Хлеб-соль" (literally "bread-salt"). Deeply ingrained in the Slavic psyche, it designates the welcome traditionally offered to newcomers, important guests or newly weds: a loaf of bread and some salt.

Today, bread is still a staple in many countries. It may play a less central role in the diet of other nations, including France, but often remains an essential part of their cultural identity as attested by French designer Jean-Paul Gautier's 2005 fashion collection Paris-Couture (the video is in French but the fun is in the watching). Although nobody wore bread to KCW (alas!), bread love was everywhere...

...in the heady fragrance of wheat...

Still, Richard Miscovich who teaches artisan baking at Johnson & Wales University in Providence, Rhode Island, and champions wood-fired ovens, encouraged bakers to go beyond bread and use the full range of temperatures such ovens offer as they gradually release heat. I didn't attend the class but I heard people raving about it afterwards and from what they were saying, no oven will be allowed to cool empty from now on if it can be helped...

When all is said and told, holding an event such as the Kneading Conference is a lot like sowing: you get to scatter seeds all around, some drop into awaiting furrows, some blow with the wind, others still travel with birds to faraway places. But wherever they finally fall, all of them carry the promise of growth. I am deeply grateful to KCW's sponsors as well as to the organizers, instructors, volunteers and WSU staff members who unreservedly shared their knowledge and skills. You guys rock! Thank you.

The only downside to such inspiring events is that they are also exercises in frustration! Take a look at the schedule for this year and tell me you wouldn't have be tempted by pretty much each and every one of these lectures, classes, workshops, and visits. I know I was. Never more than at a Kneading Conference do I regret that human beings haven't been graced with the gift of ubiquity. Oh, well...

In 2011 and even more so in 2012, I followed the grain, trying to get a better idea of the ways bakers could help revive and sustain farms in their communities by sourcing ingredients close to home and learning to work with heritage crops, "liberating" the aromas of their terroir in the process. This year, I went for the bread.

I picked the two-day class on creating signature breads, taught by Martin Philip, a baker and the bakery operations manager at King Arthur Flour in Norwich, Vermont (more on the class in an upcoming post).

I also picked the hamburger workshop taught by Mel Darbyshire, head baker for Grand Central Bakery in Seattle. The focus was on developing buns that would be both handsome and wholesome, and Mel nailed it for sure. I never knew such plump and tasty beauties could actually be good for you! I'll post pictures and the formula as soon as I can.

Finally, on the last day, I sat in for a fantastic lesson on the science of bread, taught by Lee Glass, a passionate home baker and a physician with a keen interest in the chemistry that underlies baking. While I took copious notes, I would be hard put to convey what I heard in a comprehensive and scientifically meaningful manner. So I won't attempt it. Instead and with Lee's help (which he kindly agreed to provide), I will try to put together a few posts on what goes on behind the scene at various stages of baking. If all goes well, it will be a project for the long winter months.

The Conference wasn't entirely focused on technique and science though. Other participants chose different classes. For a broader perspective (and way more pictures since operating the camera with a cast turned out to be a bit of a challenge), you may want to check out the links provided at the bottom of this post.

Darra Goldstein kickstarted the Conference with a welcome reminder of bread culture through the ages. I already knew Goldstein, who teaches Russian at Williams College and is a founding editor of Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture, as the author of A La Russe: A Cookbook of Russian Hospitality, a marvelously nostalgic book which followed me cross-country when we moved west. But I didn't know she was also a bread aficionada (she even owns and operates an Alan Scott wood-fired oven).

There was fervor in her voice as she evoked the traditional Russian stove: made of brick and covered with stucco, it can fire to a very high temperature and since it releases heat very slowly, it can be used reliably for a variety of dishes as it cools. First comes the rye bread, dark and fragrant, then soups and porridges, and finally when the heat is almost a memory, the fermented dairy products.

Slow and beautiful, the stove was always seen as a life-giving force and controlling it was an art. But it would be a mistake to romanticize bread: much of Europe was always on the verge of famine. Putting a loaf on the table required a lot of manpower and was back-breaking work, often done in the dark bakeshops where the only light came from the oven, as attested in the work of numerous painters, notably Millet in France.

Recalling how difficult it had been for her to adjust to life in the Soviet Union as a graduate student, Goldstein said the only thing that kept her from flying back home was Russian hospitality or "Хлеб-соль" (literally "bread-salt"). Deeply ingrained in the Slavic psyche, it designates the welcome traditionally offered to newcomers, important guests or newly weds: a loaf of bread and some salt.

Today, bread is still a staple in many countries. It may play a less central role in the diet of other nations, including France, but often remains an essential part of their cultural identity as attested by French designer Jean-Paul Gautier's 2005 fashion collection Paris-Couture (the video is in French but the fun is in the watching). Although nobody wore bread to KCW (alas!), bread love was everywhere...

...in the heady fragrance of wheat...

Still, Richard Miscovich who teaches artisan baking at Johnson & Wales University in Providence, Rhode Island, and champions wood-fired ovens, encouraged bakers to go beyond bread and use the full range of temperatures such ovens offer as they gradually release heat. I didn't attend the class but I heard people raving about it afterwards and from what they were saying, no oven will be allowed to cool empty from now on if it can be helped...

When all is said and told, holding an event such as the Kneading Conference is a lot like sowing: you get to scatter seeds all around, some drop into awaiting furrows, some blow with the wind, others still travel with birds to faraway places. But wherever they finally fall, all of them carry the promise of growth. I am deeply grateful to KCW's sponsors as well as to the organizers, instructors, volunteers and WSU staff members who unreservedly shared their knowledge and skills. You guys rock! Thank you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)